Summary

Current: Governor since 2017

Affiliation: Republican

Next Election:

History: Phil Scott’s father was disabled after being wounded while serving in World War II and later worked as a vehicle permit supervisor for the state highway department. Scott became a co-owner of DuBois Construction in 1986. He is a past president of the Associated General Contractors of Vermont

Phil Scott was a representative for the Washington District in the Vermont Senate from 2001 to 2011 and the 81st lieutenant governor from 2011 to 2017.

Quotes: Not only would the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework make the U.S. more competitive, create good paying jobs and help modernize our country, but it would also be a much-needed moral victory for a very polarized nation. I hope Congress acts ASAP.

Featured Video: Governor Scott’s 2021 Inaugural Address

OnAir Post: Phil Scott – VT

News

About

Source: Government page

Phil Scott became the 82nd Governor of Vermont in January 2017. As Governor, he is committed to making a difference in the lives of Vermonters by growing the state’s economy, making Vermont more affordable, and protecting the most vulnerable.

Phil Scott became the 82nd Governor of Vermont in January 2017. As Governor, he is committed to making a difference in the lives of Vermonters by growing the state’s economy, making Vermont more affordable, and protecting the most vulnerable.

Throughout his years of public service, Phil has listened to, and learned from Vermonters, and is always willing to roll up his sleeves to help get the job done.

Phil has consistently focused on economic and affordability issues. During his first two legislative sessions as Governor, he worked with the Legislature to ensure the Fiscal Year 2018 & 2019 General Fund budgets did not raise a single tax or fee, and made critical investments in economic and workforce development, workforce housing, childcare and early learning, career technical training, higher education, clean water, addressing the opioid crisis and more.

Previously, he was elected and served three terms (2011-2017) as Vermont’s 79th Lieutenant Governor. In this role, he launched the Everyday Jobs Initiative – where he worked in 35 different professions around the state – and Vermont Economy Pitch sessions for the opportunity to learn from Vermont’s employers and workers. In 2011, in the wake of Tropical Storm Irene, he organized the removal and disposal of mobile homes around the state, which were destroyed by the flood, all at no cost to homeowners and without spending any taxpayer dollars.

Prior to that role, he was elected to the Vermont Senate for five terms, representing Washington County. During his 10-year service in the Senate, he was Vice Chair of the Transportation Committee and Chair of the Institutions Committee.

Phil is also active in community service projects. In 2005, he founded the Wheels for Warmth program, which allows Vermonters to donate tires they no longer need. The tires that meet state inspection standards are offered for resale at affordable prices, with all proceeds benefiting heating fuel assistance programs. The program has raised more than $428,000 for emergency fuel assistance, sold nearly 19,000 safe donated tires, and recycled more than 31,000 unsafe tires.

For more than thirty years, Phil was a co-owner of his family construction business, and he still races the #14 car at Barre’s Thunder Road, where he has the most career wins as a Late Model driver at the track. He’s also an avid cyclist.

He is a lifelong Vermonter who grew up in Barre and graduated from Spaulding High School and the University of Vermont. He lives in Berlin with his wife Diana McTeague Scott, and has two grown daughters, Erica and Rachael.

Personal

Full Name: Phillip ‘Phil’ B. Scott

Gender: Male

Family: Wife: Diana; 2 Children: Erica, Rachael

Birth Date: 08/04/1958

Birth Place: Barre, VT

Home City: Berlin, VT

Source: Vote Smart

Education

BASc, Industrial Education, University of Vermont, 1976-1980

Political Experience

Candidate, Governor of Vermont, 2022

Governor, State of Vermont, 2017-Present

Lieutenant Governor, State of Vermont, 2011-2017

Senator, Vermont State Senate, District Washington, 2001-2011

Professional Experience

Late Model Driver, Barre’s Thunder Road International Speedbowl, 1992-present

Co-Owner, Shoney’s Restaurant

Co-Owner/Vice-President, DuBois Construction Incorporated, 1984-2016

Office

Office of Governor Phil Scott

109 State Street, Pavilion

Montpelier, VT 05609

Phone: 802 828-3333 (TTY: 800 649-6825)

Fax: 802 828-3339

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

To learn more, go to this wikipedia section in this post.

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

New Legislation

More Information

Wikipedia

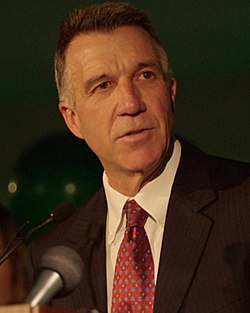

Philip Brian Scott (born August 4, 1958) is an American politician, businessman, and stock car racer who has been the 82nd governor of Vermont since 2017. A member of the Republican Party, he was a representative for the Washington District in the Vermont Senate from 2001 to 2011 and served as the 81st lieutenant governor of Vermont from 2011 to 2017.

Scott was first elected governor of Vermont in the 2016 general election,[1] and was reelected in 2018, 2020, 2022, and 2024. Scott’s 2024 margin of victory is the largest in any Vermont gubernatorial election since 1946.[2] As of 2025, Scott is the second-longest serving incumbent governor in the U.S.

One of the nation’s most popular governors,[3] Scott is often described as a moderate Republican.

Early life

Philip B. Scott was born on August 4, 1958, in Barre, Vermont, the son of Marian (Beckley) and Howard Roy Scott (1914–1969).[4][5] His father was disabled after being wounded while serving in World War II and later worked as a vehicle permit supervisor for the state highway department.[6][7] In 1973, Scott’s mother married Robert F. Dubois (1919–1983).[8][9]

Scott graduated from Barre’s Spaulding High School in 1976.[10] Scott is a 1980 graduate of the University of Vermont, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in industrial education.[11]

Business career

After graduating from high school, Scott began working at DuBois Construction, a Middlesex business founded by the brother of his mother’s second husband.[12] After college, Scott owned a motorcycle sales and repair shop in Morrisville, then worked as a construction manager for Morrisville’s H. A. Manosh Corporation.[13] Scott has also been involved in other business ventures, including ownership of a restaurant and a nightclub.[14]

Scott became a co-owner of DuBois Construction in 1986.[15][16] He is a past president of the Associated General Contractors of Vermont.[16] On January 6, 2012, a fire at DuBois Construction caused substantial damage,[17][18] but the owners rebuilt and continued operations.[19]

After being elected governor, Scott sold his share of DuBois Construction to avoid possible conflicts of interest, since DuBois Construction does business with the State of Vermont. He sold his 50% share for $2.5 million plus 3% interest, payable over 15 years.[20] Scott said he opted to finance the sale himself rather than having the company borrow the money to pay him in full to preserve the company’s bonding capacity.[20] Critics suggested that Scott’s sale of his share in the company over 15 years did not eliminate possible conflicts of interest, but Scott and the attorney who negotiated the sale on his behalf disagreed.[20]

In October 2018, the state ethics commission issued an advisory opinion that Scott did have a conflict of interest because of his continued connection to the company.[21] In September 2019, the commission withdrew the opinion, with its executive director saying that the process for receiving the complaint and investigating and issuing the opinion had been flawed.[21] In February 2022, DuBois executives said they had reached an agreement to sell the company to Barrett Trucking of Burlington.[22] The sale’s terms were not disclosed, including whether Scott would receive a lump sum or installment payments, but DuBois representatives said the company’s obligation to Scott would be met.[22]

Political career

Vermont Senate

A Republican, Scott was elected to the Vermont Senate in 2000, one of three at-large senators representing the Washington County Senate district. He was reelected four times, and was in office from 2001 to 2011. During his Senate career, he was vice chair of the Transportation Committee and chaired the Institutions Committee. He also was a member of the Natural Resources and Energy Committee.[23] As chair of the Institutions Committee, Scott redesigned the Vermont State House cafeteria to increase efficiency.[24]

During his time in the Senate, Scott was on several special committees, including the Judicial Nominating Board, the Legislative Advisory Committee on the State House, the Joint Oversight Corrections Committee, and the Legislative Council Committee.[25]

Lieutenant governor

On November 2, 2010, Scott was elected the 81st lieutenant governor of Vermont,[26] defeating Steve Howard. He took office on January 6, 2011. He was reelected in 2012, defeating Cassandra Gekas, and in 2014, defeating Dean Corren.

As lieutenant governor, Scott presided over the Vermont Senate when it was in session. In addition, he was a member of the committee on committees, the three-member panel that determines Senate committee assignments and appoints committee chairs and vice chairs. In the event of a tie vote, Scott was tasked with casting a tie-breaking vote. He also was acting governor when the governor was out of state.[27]

As a state senator and lieutenant governor, Scott was active with a number of community service projects. In 2005, he founded the Wheels for Warmth program, which buys used car tires and resells safe ones, with the profits going to heating fuel assistance programs in Vermont.[28]

Job approval as lieutenant governor

In September 2015, Scott maintained high name recognition and favorability among Vermonters. The Castleton University Polling Institute found that more than three-quarters of Vermonters knew who he was, and that of those who were able to identify him, 70% viewed him favorably.[29] Despite his being a Republican, the same poll found that 59% of self-identified Democrats held a favorable view of Scott, while only 15% held an unfavorable view of him.[29]

National Lieutenant Governors Association

Scott was an active member of the National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA), and was on the NLGA’s executive committee and the NLGA’s finance committee.[30][31] As a member of the NLGA, he joined fellow lieutenant governors across the country in two bipartisan letters opposing proposed cuts to the Army National Guard in 2014 and 2015.[32][33] Scott was a lead sponsor of an NLGA resolution to develop a long-term vision for surface transportation in the U.S.[34] He also co-sponsored resolutions to recognize the importance of arts and culture in tourism to the U.S. economy, to support Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education, to support designating a National Arts in Education Week, and to support a comprehensive system to end homelessness among U.S. veterans.[35][36][37][38]

Governor of Vermont

2016 gubernatorial campaign

In September 2015, Scott announced his candidacy for Vermont governor.[39]

An early 2016 poll commissioned by Vermont Public Radio and conducted by the Castleton University Polling Institute found that of the two candidates for the Republican nomination for governor, Scott was preferred by 42% of respondents compared to 4% for Bruce Lisman.[40] A poll commissioned by Energy Independent Vermont in late June 2016 indicated that Scott had the support of 68% of Republicans to Lisman’s 23%.[41]

On May 8, 2016, Scott was endorsed by nearly all of Vermont’s Republican legislators.[42] He did not support Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential campaign.[43]

On August 9, Scott defeated Lisman in the primary election by 21 percentage points.[44] He defeated Sue Minter, the Democratic nominee, in the November general election by 8.7 percentage points.[45][46]

Governorship

Fraud case settlement

On April 13, 2017, Scott announced a $150 million settlement with Raymond James Financial, Inc. as part of resolving fraud allegations by contractors and investors related to the Jay Peak and Burke Mountain EB-5 developments.[47]

Job approval

According to an October 2017 Morning Consult poll, Scott’s approval rating stood at 60%, making him the 7th most popular governor in the country. The poll was conducted between July 1 and September 30, 2017, and had a margin of error of 4%. In April 2018, another Morning Consult poll found that Scott’s approval rating had risen to 65%, making him the 4th most popular governor in the country.[48] His favorability ratings fell to 52% by May 2018,[49] and to 47% by July, marking the largest decrease in popularity for any governor in the nation.[50] By April 2019, Scott’s approval rating had recovered to 59%, with a 28% disapproval rating, making him the 5th most popular governor in the country, with a net approval of 31%.[51]

Political positions

Scott has been called a moderate,[52][53] as well as a liberal Republican.[54] His views are “fiscally conservative but socially liberal“.[55][56] Scott has said: “I am very much a fiscal conservative. But not unlike most Republicans in the Northeast, I’m probably more on the left of center from a social standpoint … I am a pro-choice Republican”.[57] He supported the impeachment inquiry into Donald Trump that began in September 2019,[58] and called for Trump to “resign or be removed from office” after the 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol building.[59] In the 2020 and 2024 presidential elections, Scott announced he voted for Democratic nominees Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, respectively,[60][61] calling the latter “a vote against Donald Trump” and a move to “put country over party”.[61]

Fiscal and budgetary issues

Scott pledged to veto any budget that grows faster than the growth rate of the underlying economy or wages in the previous year, or that increases statewide property taxes. Conflicts over raising property tax rates, which the state legislature supported and Scott opposed, led to a strained relationship between him and the legislature in 2018 for the FY19 budget, despite high revenues overall.[62]

Scott made addressing Vermont’s long-term unfunded liabilities a priority, and worked with State Treasurer Beth Pearce to pay down Vermont’s pension debt.[63]

Taxes and fees

The FY18 budget Scott signed into law did not include any new or increased taxes or fees. He has said that he opposes any new taxes.[64] He also refused to sign a bill that would have raised property taxes.[65] Scott vetoed the FY19 budget twice before allowing it to go into law without his signature, as the threat of a government shutdown approached.[66][67]

In early 2018, Scott called for eliminating the tax on Social Security benefits. House legislators incorporated a modified form of this proposal into the final FY19 budget, eliminating the tax for low- and middle-income retirees.[68] The tax reform Scott planned (which was ultimately implemented) also lowered state income tax rates by 0.2% for all brackets; tied Vermont’s tax system to Adjusted Gross Income (AGI); created Vermont-defined income deductions and personal exemptions similar to the federal tax code; increased the state earned income tax credit by three percentage points; and added a new 5% charitable contribution tax credit.[69] Scott’s administration has reduced both Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Insurance tax rates.[70] He has twice proposed to phase out the tax on military retirement income, which the legislature did not advance.[71][72]

Economic development

In 2016, Scott set a goal of boosting the state’s economy by increasing the state’s population to 700,000 within 10 years by encouraging young people who come to study in the state to remain after graduation.[73] University of Vermont economics professor Arthur Woolf Scott suggested that retention of older Vermonters, with larger incomes and tax revenues, would be a better focus, but Scott pointed to the lower average healthcare costs associated with a younger population.[74]

Scott’s economic development plan has largely focused on workforce development and economic incentives. He has advocated and achieved increasing tax credits for development, new support for small business, additional initiatives for rural economic growth, tax increment financing, permitting reform, and tax exemptions in key industries.[75] Scott has made expanding the labor force a priority of his administration, and has proposed and achieved initiatives that invest in workforce recruitment, retention, and relocation.[76]

Healthcare

Scott signed a bill requiring Vermonters to have health insurance, making Vermont among a few states to implement such a policy after the federal repeal of the individual mandate provision of the Affordable Care Act.[77] But in part due to his opposition to a financial penalty for an individual mandate, the legislature passed and Scott signed a bill that would simply require attestation of health insurance.[78]

Scott has advocated moving away from a fee-for-service-based healthcare system, and has suggested focusing more on the quality of care and services rendered. This model has been implemented on a pilot basis with an accountable care organization.[79]

In April 2021, Bryan Kehl and Christopher Rufo, among others, criticized Scott for implementing a race-based COVID-19 vaccination schedule.[80] In response, he released a statement condemning what he called a “racist response” to the plan.[81]

Education

Scott has called for modifying Act 46 to improve cost containment measures, incorporate property tax reduction, preserve local control and school choice, and allow communities to keep the funds they save through school district mergers.[82] He has expressed support for flexible learning plans and new technologies to improve educational outcomes.[82]

Scott’s FY18 budget made investments in education, including a $3 million increase in the base appropriation to the Vermont State Colleges to stabilize tuition and a new position in the Agency of Education focused on career and technical education.[83] The budget also expanded a base appropriation for child care financial assistance by $2.5 million.[84] The FY20 budget Scott signed into law built on these investments, with an additional $7.4 million for child care and $3 million more for higher education.[85] The next year, Scott worked with the legislature to eliminate tuition for members of the Vermont National Guard.[84]

As a state senator, Scott voted for legislation to reduce education property tax rates.[86][87] Scott’s FY18 budget froze property tax rates, and the FY19 budget froze residential property tax rates.[83][69]

In July 2025, Scott signed an education reform bill, marking a transitional shift in the Vermont public school system.[88]

Gun law

Scott passed legislation that banned bump stock devices, expanded background checks for gun purchases, raised the age to purchase firearms to 21 (with certain exceptions), limited the sale of certain high-capacity magazines, increased restrictions on the sale of firearms to alleged domestic abusers, and created risk protection orders.[89] In September 2018, Scott created a Violence Prevention Task Force, ordered a security assessment of all Vermont schools, and signed legislation appropriating $5 million for school security grants.[90] Scott also signed gun control legislation that “limits some aspects of gun possession and empowers authorities to remove guns from people who may be dangerous.”[91]

Government reform and modernization

Scott supports limiting Vermont’s annual legislative session to 90 days. According to him, the session’s unpredictable length discourages everyday Vermonters from running for office.[92] A 90-day session, according to Scott, would encourage more people to run for elected office by setting clear parameters.[92] Furthermore, he argues that a 90-day session would force the legislature to focus on key fiscal and operational issues.[92]

As governor, Scott created a Government Modernization and Efficiency Team to implement efficiency audits, strengthen IT planning, implement a digital government strategy, and identify opportunities to eliminate inefficiencies, establish clear metrics and streamline services.[93] He also created the Program to Improve Vermont Outcomes Together (PIVOT) initiative, which asks frontline state employees for ways to make state government systems more efficient and easier to use.[83] Scott consolidated IT functions in state government with the creation of the Agency of Digital Services, saving $2.19 million.[83][94] He also merged the Department of Liquor Control and the Lottery Department into the Department of Liquor and Lottery to achieve savings.[94] Scott’s administration has worked to achieve internal improvements through lean training and permit process improvements.[94] He also successfully sought to eliminate and merge redundant boards, commissions, studies and reports.[94]

Transportation

In July 2016, Scott outlined the transportation priorities he would implement as governor.[95] He said he would strengthen the link between economic growth and Vermont’s infrastructure; oppose additional transportation taxes, including a carbon tax; oppose accumulating additional state debt for transportation; encourage innovation in transportation by implementing a Research and Development (R&D) tax credit and an Angel Investor tax credit (a 60% credit toward cash equity investments in Vermont businesses, specifically targeted toward transportation, energy and manufacturing firms); protect the state’s transportation fund to ensure it is used for transportation purposes only; advocate federal reforms and flexibility in transportation policy; and update the Agency of Transportation’s long-range plan for transportation.

Abortion

Scott is pro-choice. In June 2019, he signed into law an abortion rights bill that was among the most wide-ranging in the U.S. in providing for abortion at any time, protecting “the fundamental right of every individual who becomes pregnant to choose to carry a pregnancy to term, to give birth to a child, or to have an abortion.”[96] In June 2022, Scott expressed his disappointment over the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and announced that a constitutional amendment to safeguard abortion rights would appear on the November ballot. In December 2022, he signed a constitutional amendment passed by Vermont voters to further protect the right to abortion in the state.[97]

LGBT

Scott supports same-sex marriage.[98] He signed into a law a gender-neutral bathroom bill intended to recognize the rights of transgender people.[99] Of the new law, he said, “Vermont has a well-earned reputation for embracing equality and being inclusive”.[100]

Drugs

On May 24, 2017, Scott vetoed a bill that would have legalized marijuana recreationally in Vermont.[101] In October 2020, he announced he would not veto another bill to legalize recreational marijuana use, allowing the bill to become a law without his signature.[102]

As governor, Scott created an Opioid Coordination Council, appointed a director of drug policy and prevention, and convened a statewide summit on growing the workforce to support opioid and substance abuse treatment.[83] To further treatment options, he worked with the Secretary of State’s Office of Professional Regulation to streamline the licensing process for treatment professionals.[103] Scott boosted efforts to reduce the drug supply through the Vermont Drug Task Force, Drug Take Back days, and expanding prescription drug disposal sites.[103]

Immigration

Scott opposed the Trump administration’s immigration policies. In 2017, he signed a bill to limit the involvement of Vermont police with the federal government regarding immigration,[104] and the Department of Justice notified Vermont that it had been preliminarily found to be a sanctuary jurisdiction on November 15, 2017.[105] Scott opposed the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy and the separation of families at the border.[106]

Environmental issues

Scott approved $48 million for clean water funding in 2017.[107] He signed an executive order creating the Vermont Climate Action Commission.[108] Scott announced a settlement with Saint-Gobain to address water quality issues and PFOA contamination in Bennington County.[109] His FY18 budget proposal called for a tax holiday on energy efficient products and vehicles.[110] On June 2, 2017, Scott led Vermont to join the United States Climate Alliance, after President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement.[111] Scott committed to achieving 90% renewable energy by 2050.[112] In 2019, he signed several pieces of legislation related to water quality, including creating a long-term funding mechanism for cleaning up the state’s waterways, testing for lead in schools and child care centers, and regulating perfluorooctanoic acid and related PFAS chemicals in drinking water.[113][114][115] On September 15, 2020, Scott vetoed the Global Warming Solutions Act, which mandated reductions to Vermont’s carbon emissions.[116] Ten days later, his veto was overridden.[117]

Racing career

Scott is a champion stock car racer.[16] He won the 1996 and 1998 Thunder Road Late Model Series (LMS) championships and the 1997 and 1999 Thunder Road Milk Bowls.[16] (The Milk Bowl is Thunder Road’s annual season finale.)[16]

In 2002, he became a three-time champion, winning both the Thunder Road and Airborne Late Model Series track championships and the American Canadian Tour championship.[16] (Airborne Park Speedway is a stock car track in the town of Plattsburgh, New York).[118] He also competed in the 2005 British Stock Car Association (BriSCA) Formula One Championship of the World, but did not finish.[119]

On July 6, 2017, Scott won the Thunder Road Late Model Series feature race; he started from the pole, and the victory was his first since 2013.[120] He participated in a limited number of Thunder Road events in 2019, and won the June 27, 2019, LMS feature race.[121] In July 2022, Scott competed in the Governor’s Cup 150, in which he finished 23rd.[122] As of July 2019, he has 31 career wins, which places him third all time in Thunder Road’s LMS division.[123]

Personal life

Scott has been married three times, first to Jane Manosh, and later to Angela Wright.[124][125] He lives in Berlin, Vermont, with his wife Diana McTeague Scott.[126] He has two adult daughters.[126][127]

Electoral history

2024

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 23,173 | 98.10 | |

| Write-in | 448 | 1.90 | ||

| Total votes | 23,621 | 100.00 | ||

| Republican | Undervotes | 1,357 | ||

| Republican | Overvotes | 7 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 266,428 | 73.60 | ||

| Democratic/Progressive | Esther Charlestin | 79,217 | 21.88 | ||

| Independent | Kevin Hoyt | 9,362 | 2.59 | ||

| Green Mountain Peace and Justice | June Goodband | 4,511 | 1.25 | ||

| Independent | Poa Mutino | 2,414 | 0.67 | ||

| Write-in | 81 | 0.02 | |||

| Total votes | 362,013 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

2022

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 20,319 | 68.56 | |

| Republican | Stephen C. Bellows | 5,402 | 18.22 | |

| Republican | Peter Duval | 3,627 | 12.24 | |

| Write-in | 290 | 0.98 | ||

| Total votes | 29,638 | 100.00 | ||

| Republican | Blank votes | 911 | ||

| Republican | Overvotes | 11 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 201,113 | 71.29 | ||

| Democratic/Progressive | Brenda Siegel[a] | 67,946 | 24.09 | ||

| Independent | Kevin Hoyt | 6,007 | 2.13 | ||

| Independent | Peter Duval | 4,714 | 1.67 | ||

| Independent | Bernard Peters | 2,307 | 0.82 | ||

| Total votes | 282,087 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

2020

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 42,275 | 72.67 | |

| Republican | John Klar | 12,762 | 21.94 | |

| Republican | Emily Peyton | 970 | 1.67 | |

| Republican | Douglas Cavett | 966 | 1.66 | |

| Republican | Bernard Peters | 772 | 1.33 | |

| Write-in | 426 | 0.73 | ||

| Total votes | 58,171 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 248,412 | 68.49 | +13.30 | |

| Progressive | David Zuckerman | 99,214 | 27.35 | −12.90 | |

| Independent | Kevin Hoyt | 4,576 | 1.26 | N/A | |

| Independent | Emily Peyton | 3,505 | 0.97 | N/A | |

| Independent | Erynn Hazlett Whitney | 1,777 | 0.49 | N/A | |

| Independent | Wayne Billado III | 1,431 | 0.39 | N/A | |

| Independent | Michael A. Devost | 1,160 | 0.32 | N/A | |

| Independent | Charly Dickerson | 1,037 | 0.29 | N/A | |

| Write-in | 1,599 | 0.44 | N/A | ||

| Total votes | 362,711 | 100.00 | +32.33 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

2018

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 24,042 | 66.67 | |

| Republican | Keith Stern | 11,617 | 32.22 | |

| Write-in | 401 | 1.11 | ||

| Total votes | 36,060 | 100.00 | ||

| Republican | Blank votes | 700 | ||

| Republican | Overvotes | 20 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 151,261 | 55.19 | +2.28 | |

| Democratic | Christine Hallquist | 110,335 | 40.25 | −3.91 | |

| Independent | Trevor Barlow | 3,266 | 1.19 | N/A | |

| Independent | Charles Laramie | 2,287 | 0.83 | N/A | |

| Independent | Cris Ericson | 2,129 | 0.78 | N/A | |

| Earth Rights | Stephen Marx | 1,855 | 0.68 | N/A | |

| Liberty Union | Emily Peyton | 1,839 | 0.66 | −2.17 | |

| Write-in | 1,115 | 0.41 | -0.31 | ||

| Total votes | 274,087 | 100.00 | N/A | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

2016

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott | 27,669 | 60.50 | |

| Republican | Bruce Lisman | 18,055 | 39.50 | |

| Write-in | 48 | 0.22 | ||

| Total votes | 45,772 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott | 166,249 | 52.95 | ||

| Democratic | Sue Minter | 138,935 | 44.25 | ||

| Liberty Union | Bill Lee | 8,808 | 2.81 | ||

| Total votes | 313,992 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican gain from Democratic | |||||

2014

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 15,282 | 99.19 | |

| Write-in | 125 | 0.81 | ||

| Total votes | 15,407 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 118,949 | 62.14 | ||

| Progressive | Dean Corren | 69,005 | 36.05 | ||

| Liberty Union | Marina Brown | 3,347 | 1.75 | ||

| Write-in | 115 | 0.06 | |||

| Total votes | 191,416 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

2012

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 9,262 | 99.69 | |

| Write-in | 29 | 0.31 | ||

| Total votes | 9,291 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 162,787 | 57.11 | ||

| Democratic | Cassandra Gekas | 115,015 | 40.35 | ||

| Liberty Union | Ben Mitchell | 6,975 | 2.45 | ||

| Write-in | 257 | 0.09 | |||

| Total votes | 285,034 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

2010

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott | 15,981 | 56.12 | |

| Republican | Mark Snelling | 12,389 | 43.51 | |

| Write-in | 105 | 0.37 | ||

| Total votes | 28,475 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott | 116,198 | 48.98 | ||

| Democratic | Steve Howard | 99,843 | 42.45 | ||

| Independent | Peter Garritano | 8,627 | 3.67 | ||

| Progressive | Marjorie Power | 8,287 | 3.52 | ||

| Liberty Union | Boots Wardinski | 2,228 | 0.95 | ||

| Total votes | 235,183 | 100.00 | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

2008

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 15,763 | 21.20 | |

| Democratic | Ann Cummings (incumbent) | 15,291 | 20.57 | |

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 15,089 | 20.30 | |

| Democratic | Kimberly B. Cheney | 11,673 | 15.71 | |

| Democratic | Laura Day Moore | 10,847 | 14.59 | |

| Republican | John R. Gilligan | 5,660 | 7.62 | |

| Total votes | 74,323 | 100.00 | ||

2006

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Ann Cummings (incumbent) | 14,416 | 20.47 | |

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 12,994 | 18.45 | |

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 12,595 | 17.89 | |

| Democratic | Kimberly B. Cheney | 11,685 | 16.59 | |

| Democratic | Denny Osman | 11,154 | 15.84 | |

| Republican | Jim Parker | 7,573 | 10.76 | |

| Total votes | 70,417 | 100.00 | ||

2004

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 16,274 | 21.08 | |

| Democratic | Ann Cummings (incumbent) | 16,134 | 20.90 | |

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 13,294 | 17.22 | |

| Democratic | Kimberly B. Cheney | 13,064 | 16.92 | |

| Democratic | Michael Roche | 9,242 | 11.97 | |

| Republican | J. Paul Giuliani | 9,194 | 11.91 | |

| Total votes | 77,202 | 100.00 | ||

2002

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 13,017 | 21.94 | |

| Democratic | Ann Cummings (incumbent) | 11,213 | 18.90 | |

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 10,849 | 18.28 | |

| Republican | J. Paul Giuliani | 8,982 | 15.14 | |

| Democratic | Kimberly B. Cheney | 8,450 | 14.24 | |

| Democratic | Charles Phillips | 6,822 | 11.50 | |

| Total votes | 59,333 | 100.00 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 1,725 | 31.86 | |

| Republican | J. Paul Giuliani | 1,556 | 28.74 | |

| Republican | Phil Scott (incumbent) | 1,547 | 28.57 | |

| Republican | George Corey | 587 | 10.84 | |

| Total votes | 5,415 | 100.00 | ||

2000

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Bill Doyle (incumbent) | 15,298 | 20.51 | |

| Republican | Phil Scott | 13,412 | 17.98 | |

| Democratic | Ann Cummings | 12,220 | 16.39 | |

| Republican | J. Paul Giuliani | 11,997 | 16.09 | |

| Democratic | Warren F. Kitzmiller | 11,378 | 15.26 | |

| Democratic | Paul N. Poirier | 10,276 | 13.78 | |

| Total votes | 74,581 | 100.00 | ||

Notes

- ^ Candidate received the nominations of both the Democratic and Progressive parties and was listed on the ballot as “Democratic/Progressive” (candidate is primarily a Democrat).

References

- ^ “Vermont Election Results”. Vermont Secretary of State. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Heintz, Paul. “Scott’s Victory Lap: Gov Wins Third Term, Gray Elected LG, Speaker Johnson Falls Short”. Seven Days. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ eyokley (November 18, 2021). “Why the Country’s Most Popular Governor May Be Resisting the GOP’s Calls to Run for Senate in Vermont”. Morning Consult. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ “Vermont Statewide Races: Governor”. Election 2016. South Burlington, VT: WCAX-TV. 2016. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ “Search | the University of Vermont”.

- ^ “Obituary, Howard R. Scott”. Barre Montpelier Times Argus. Barre, VT. December 3, 1969. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lyman, Dorothy (December 22, 1969). “What Others Say: A Tribute to Howard R. Scott”. Barre Montpelier Times Argus. Barre, VT. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Obituary, Robert F. DuBois”. The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, VT. April 28, 1983. p. 2B – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Vermont Marriage Records, 1909-2008, Entry for Robert Farnam Dubois and Marion Scott”. Ancestry.com. Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com LLC. 1974. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Savage, Katy (October 1, 2015). “Milne Cedes Gov. Run To Friend Scott”. Vermont Standard. Woodstock, VT. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ “Phil Scott Says Yes at Labor Day Parade in Northfield”. Northfield News. Northfield, VT. September 17, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Hewitt, Elizabeth (January 13, 2017). “Governor Details Construction Company Sale”. VT Digger. Montpelier, VT. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ McCullum, April (February 28, 2017). “Scott seeks reform of Act 250, which he says foiled shop plan”. The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, VT. p. A4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Career Spotlight: Phil Scott”. The Burlington Free Press: Business Monday. Burlington, VT. December 23, 1996. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, Mark (September 25, 2016). “Updated: Scott to sell share in construction firm if elected governor”. VT Digger. Montpelier, VT. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f “Phil Scott Says Yes at Labor Day Parade in Northfield – www.thenorthfieldnews.com – Northfield News”. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ |topnews|text|FRONTPAGE Newspaper article, Building of Construction Firm Owned by Vermont Lieutenant Governor Burns in Middlesex[permanent dead link], burlingtonfreepress.com, January 6, 2012.

- ^ “Fire Engulfs DuBois Construction Headquarters” Archived January 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Barre-Montpelier Times Argus, January 6, 2012

- ^ Aloe, Jess (September 24, 2016). “Phil Scott will sell share in business if elected”. Burlington Free Press. Burlington, VT.

- ^ a b c Governor Details Construction Company Sale.

- ^ a b Rathke, Lisa (September 5, 2019). “Vermont commission withdraws conflict-of-interest opinion on governor”. Valley News. Lebanon, NH. Associated Press.

- ^ a b Thys, Fred (February 14, 2022). “Company that owed Gov. Phil Scott $2.5 million is sold”. VT Digger. Monepelier, VT.

- ^ “Journal of the Vermont Senate”. leg.state.vt.us. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Phil Scott: Efficiency over big ideas”. Burlington Free Press. June 23, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ “Senator Phil Scott”. legislature.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Phil Scott elected Vermont Lieutenant Governor”. The Burlington Free Press. Associated Press. November 3, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ “About Vermont Lieutenant Governor Phil Scott | Lieutenant Governor”. ltgov.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ Keck, Nina (October 26, 2015). “Wheels For Warmth Comes To Rutland”. Vermont Public Radio. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Hirschfeld, Peter (September 21, 2015). “Castleton Poll Gives An Early Look At Vermont Gubernatorial Race”. digital.vpr.net. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Officers & Executive Committee | National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA)”. nlga.us. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Operational Committees | National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA)”. nlga.us. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “National Lieutenant Governors Association April 2014” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ “National Lieutenant Governors Association April 2015” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ “Resolution to Develop a Shared, Long Term Vision for Surface Transportation” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2017.

- ^ “Recognizing the Importance of Arts and Culture in Tourism to the Economy of the United States” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ “Resolution in Support of STEM Education Initiative” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ “Resolution in Support of Designating the Week of September 13–19, 2015 as National Arts in Education Week” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2015.

- ^ “A Resolution In Support Of Comprehensive, Coordinated Systems to End Homelessness Among Veterans” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2016.

- ^ Phil Scott to run for Governor Archived September 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, wcax.com; accessed September 13, 2015.

- ^ Butler, Taylor Dobbs, Jonathan (February 22, 2016). “The VPR Poll: The Races, The Issues And The Full Results”. digital.vpr.net. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ “Poll: Vermonters Support Action to Address Global Warming”. July 7, 2016. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ “Republican legislators endorse Phil Scott for governor | Vermont Business Magazine”. vermontbiz.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ Midura, Kyle (May 13, 2016). “Vt. candidates for governor debate in Burlington”. WCAX.COM Local Vermont News, Weather and Sports. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ “Phil Scott claims GOP primary victory for governor”. Burlington Free Press. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Aloe, Jess (August 9, 2016). “Sue Minter wins Democratic nomination for governor”. Burlington Free Press. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ “Vermont Election Results 2016: Governor Live Map by County, Real-Time Voting Updates”. Election Hub. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ “$150 Million Settlement Reached to Reimburse Jay Peak and Burke Mountain Creditors”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ “America’s Most and Least Popular Governors”. Morning Consult. October 31, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ Colin Meyn (June 11, 2018). “Scott polling almost 20% lower than before 2016 election”. vtdigger.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ “America’s Most and Least Popular Governors — July 2018”. Morning Consult. July 25, 2018. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Morning Consult’s Governor Approval Rankings”. Morning Consult. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Jacobson, Louis (August 23, 2021). “Blue, But Bipartisan: Can Vermont Be a Model for the Rest of the U.S.?”. U.S. News and World Report.

- ^ Cutler, Calvin (May 15, 2024). “Gov. Scott aims to be ‘voice’ of moderate Vermonters as he navigates party of Trump”. WCAX.com.

- ^ Richards, Parker (November 3, 2018). “The Last Liberal Republicans Hang On”. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ King, Laura (November 10, 2016). “Republican Phil Scott wins Vermont governor’s race”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “Republican Vermont Gov. Phil Scott is running for reelection to 5th term”. Associated Press. May 12, 2024.

- ^ “Governors lead a Republican renaissance in New England”. Press Herald. December 25, 2016. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “A first: Vermont GOP governor backs Trump impeachment probe”. Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Sukiennik, Greg (January 6, 2021). “Gov. Phil Scott calls on Trump to ‘resign or be removed’“. Brattleboro Reformer. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Mastrangelo, Dominick (November 3, 2020). “Vermont’s GOP governor says he voted for Biden”. TheHill. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Timotija, Filip (November 5, 2024). “Vermont’s GOP governor votes for Harris: ‘I had to put country over party’“. The Hill. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Peter (May 12, 2018). “As Lawmakers Close Out 2018 Session, Scott Vows Budget Veto”. Vermont Public Radio. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ “New Vermont state budget signed into law”. WPTZ. June 19, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Conlin, Spencer (January 24, 2018). “Governor Phil Scott outlines 2019 budget, calls on legislature to pass budget with no new taxes”. MYCHAMPLAINVALLEY. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “Vermont tax standoff: How Gov. Scott and lawmakers got to this impasse”. Burlington Free Press. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Peter (June 26, 2018). “Scott Will Allow Budget To Pass Without His Signature”. Vermont Public Radio. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Jordan, David (June 26, 2018). “Budget bill will become law without governor’s signature”. AP NEWS. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Xander Landen (July 30, 2018). “Social Security income tax exemptions are now in place”. VT Digger. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ a b “FISCAL DISCIPLINE & RESPONSIBLE TAX RELIEF | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “REDUCING COSTS FOR FAMILIES & BUSINESSES | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Gov. Scott calls for tax exemption on Social Security income”. Burlington Free Press. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Galloway, Anne; Landen, Xander (January 24, 2019). “Scott changes course on taxes and fees in budget address”. VTDigger. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Margolis: VT’s slow population growth might be the norm”. VTDigger. February 21, 2016. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ Isaacs, Abby (October 8, 2017). “Phil Scott’s economic plan looks to encourage young people to stay in Vermont”. WPTZ. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ “Economic Expansion | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “EXPANDING & STRENGTHENING VERMONT’S WORKFORCE | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Ring, Wilson (June 10, 2018). “Vermont to require that all have health insurance”. The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ “Bill Status H.524 (Act 63)”. legislature.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Supporting Safe and Healthy Communities | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Klein, Melissa (April 3, 2021). “Vermont Gov. Phil Scott slammed by critics, ex-Giant for race-based vax schedule”. New York Post.

- ^ “Scott Decries ‘Racist Response’ to BIPOC Vaccine Eligibility”. US News. April 5, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ a b “Making Vermont More Affordable – Phil Scott For Governor”. Phil Scott For Governor. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e “A Foundation for Growth | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ a b “EXPANDING & STRENGTHENING VERMONT’S WORKFORCE | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ JFO (May 2019). “FY20 Conference Committee Budget Highlights” (PDF). ljfo.vermont.gov.

- ^ “The Vermont Legislative Bill Tracking System”. leg.state.vt.us. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Legislative Documents”. leg.state.vt.us. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ “Ceremonial signing puts transformational Vermont education reform bill into law”. mynbc5.com. July 1, 2025.

- ^ “OFFICIAL STATEMENT ON S.55, S.221 & H.422 | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Supporting Safe and Healthy Communities | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Gov. Scott signs VT gun bills, calling for civility, as protesters yell ‘traitor’“. Burlington Free Press. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c “Phil Scott Announces New Legislative and Budget Initiatives – Phil Scott For Governor”. Phil Scott For Governor. May 10, 2016. Archived from the original on June 28, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “Governor’s Government Modernization and Efficiency Team (Executive Order 03-17) | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d “Modernizing State Government | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Phil Scott for Vermont Transportation Priorities – Phil Scott For Governor”. July 28, 2016. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ WCAX (June 11, 2019). “Scott signs bill that preserves right to an abortion”. wcax.com. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Vermont governor signs amendment protecting abortion rights”. AP News. December 13, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Thurston, Jack (November 7, 2012). “In liberal Vt., Republican Lt. Gov. manages win”. WPTZ. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ “Republican Gov. Phil Scott Signs Vermont Gender-Neutral Bathroom Bill Into Law”. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Croffie, Kwegyirba. “Vermont passes gender-neutral bathroom bill”. CNN. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (May 24, 2017). “Vermont governor rejects recreational pot bill”. CNNMoney. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Frias, Nikki. “‘More Work Is Needed’ Says Gov. Phil Scott After Vermont Legalizes Recreational Cannabis”. Forbes. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ a b “ADDRESSING THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Gov. Scott signs Vermont law countering Trump immigration plan”. WPTZ. Associated Press. March 28, 2017. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “Justice Department Sends Letters to 29 Jurisdictions Regarding Their Compliance with 8 U.S.C. 1373”. United States Department of Justice. November 15, 2017. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Haag, Matthew; Bidgood, Jess (June 19, 2018). “Governors Refuse to Send National Guard to Border, Citing Child Separation Practice”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “Protecting the Vulnerable” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2018.

- ^ “Vermont Climate Action Commission (Executive Order 12-17) | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ “Governor Phil Scott, Attorney General TJ Donovan and Bennington County Legislative Leaders Announce a Settlement with Saint-Gobain | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ “FY 2018 Executive Budget Summary” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2017.

- ^ “Vermont to Join US Climate Alliance”. US News. June 2, 2017. Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ “Preserving the Environment | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ “Bill Status S.96 (Act 76)”. legislature.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Governor Phil Scott Signs Lead Testing & Remediation Bill Into Law | Office of Governor Phil Scott”. governor.vermont.gov. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ “Governor Signs PFAS Protection Bill”. Vermont Public Interest Research Group. May 16, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Norton, Kit (September 15, 2020). “Scott Vetoes Global Warming Solutions Act”. VT Digger. VT Digger. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ McDermott, Maeve (September 25, 2020). “Vermont passes Global Warming Solutions Act, overriding governor’s veto”. Jurist. Jurist. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ “Home Page”. Airborne Park Speedway. Plattsburgh, NY. Archived from the original on May 14, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Phil Scott scores wire-to-wire victory”. Barre-Montpelier (Vt.) Times-Argus. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ “Scott flying high at Thunder Road”. Times Argus. Barre, VT. July 7, 2017. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Thunder Road Staff (June 27, 2019). “Dragon, Scott Add to Thunder Road Legacies on CCV Night”. Thunder Road VT.com. Barre, VT: Thunder Road Speedbowl.

- ^ “Corliss Cashes in for a Three-Peat in Vermont Lottery Governor’s Cup 150”. Thunder Road VT.com. Barre, VT. July 14, 2022.

- ^ “Vermont Governor Wins Late Model Race at Thunder Road”. Speed51.com. Concord, NC. June 28, 2019.

- ^ “Wedding Announcements: Manosh-Scott”. Barre Montpelier Times Argus. Barre, VT. April 11, 1982. p. Section 3, page 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Wedding Announcements: Scott-Wright”. Rutland Herald. Rutland, VT. February 6, 2000. p. E6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b “About Phil Scott – Early Years, Personal History & More”. Phil Scott For Governor. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ Vermont General Assembly (2001). Vermont Legislative Directory and State Manual. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Secretary of State. p. 155. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Secretary of State of Vermont (August 13, 2024). “Vermont Election Night Results”. electionresults.vermont.gov. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ “2022 Aug Primary Official Results” (PDF). Vermont Secretary of State. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ “Vermont Primary Election Results”. Vermont Secretary of State. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ “2020 Vermont Governor Results”. CNN. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “Results Vermont Governor Primary Election”. The New York Times. August 16, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “Vermont Governor Election Results 2018”. Politico. November 7, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “Vermont Primary 2016: Full Results”. Politico. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ “Vermont Election Results 2016”. The New York Times. August 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “Unofficial Results – Primary Election – August 26, 2014”. Vermont Secretary of State. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ “Vermont Election Results – 2014”. New York Times. December 17, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “2012 Lieutenant Governor Republican Primary”. Vermont Secretary of State. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ “2012 Vermont Election Results”. New York Times.

- ^ “2010 Lieutenant Governor Republican Primary”. Vermont Secretary of State. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ “2010 Vermont Elections”. New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ “VT Elections Database » 2008 State Senator General Election Washington District”. VT Elections Database. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ “VT Elections Database » 2006 State Senator General Election Washington District”. VT Elections Database. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ “VT Elections Database » 2004 State Senator General Election Washington District”. VT Elections Database. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ “VT Elections Database » 2002 State Senator General Election Washington District”. VT Elections Database. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ “VT Elections Database » 2000 State Senator General Election Washington District”. VT Elections Database. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

External links

- Governor Phil Scott official government website

- Phil Scott for Governor official campaign website

- Profile at the Vermont General Assembly (archived)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Profile at Vote Smart